Barcelona’s Other Architect, Domènech

By ANDREW FERREN - New York Times, 12/16/2010

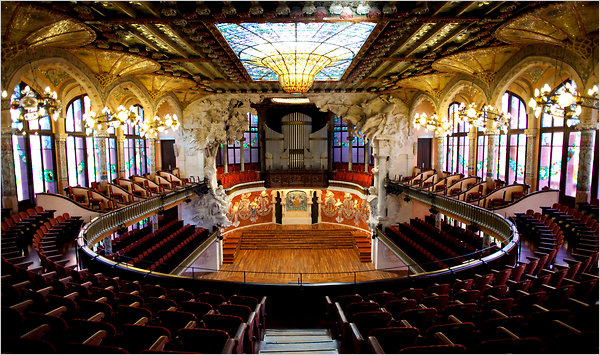

Lluís Domènech i Montaner created the dazzling 1908 Palau de la Música Catalana, a jewel of Catalan modernisme, adorning surfaces and choosing stained glass to fill the space with light.

IT’S sometimes hard to have a conversation about Barcelona that does not include the name Gaudí in it. The world is so gaga for Antoní Gaudí — the genius of Catalan modernisme (the Spanish version of Art Nouveau) whose early 20th-century buildings are virtual emblems of the city — that most of his modernista contemporaries go little noticed by tourists.

But if you’re like me, and don’t much like the structural theatrics and unbridled mannerism of Gaudí’s buildings, check out those of Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1849-1923), an under-sung hero of the movement. A journey to the three places in Catalonia where his buildings made a splash a century ago — including Barcelona — is made easier by following the Barcelona Modernisme Route, which was created in 2005. A guidebook and map of the route can be bought for 18 euros, or $23.50 at $1.31 to the euro, at several kiosks around the city, and can be viewed online at rutadelmodernisme.com.

Domènech is often hailed as the most modern of the modernistas, notably for his mastery of lightweight steel construction. Unesco, at least, doesn’t give him short shrift, having designated his most important buildings in Barcelona a World Heritage Site (just as it did with the works of Gaudí). Multifaceted and astonishingly productive, Domènech wore many hats. Besides being an architect and professor (Gaudí was his student at Barcelona’s School of Architecture), he was also a prominent politician and Catalan nationalist and a pre-eminent scholar of heraldry.

For architects, Barcelona at the turn of the 20th century was the right place at the right time. Nineteenth-century industrialization brought tremendous wealth, and between the Universal Exposition of 1888 (for which Domènech created two of the most noteworthy buildings) and the construction of the Eixample — the vast grid of streets laid out in 1859 to decongest the old city — there was a heady mix of civic pride and social ascension in the air. The rising middle class was eager to make its mark on the rapidly growing city, and the new modernista style seemed perfectly suited to this task, rife as it was with neo-Gothic motifs that linked the newly minted mercantile titans to Barcelona’s rich medieval history.

Robert Lubar, an associate professor at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, points out that, much more so than Gaudí, Domènech was influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement of Ruskin and Morris. “He believed that ‘the complete interior’ served some kind of ethical purpose,” Professor Lubar said.

Domènech’s most “complete interior” is the 1908 Palau de la Música Catalana, a stunning concert hall miraculously shoehorned into a small lot at the junction of the old city and the new. Often likened to a conductor, Domènech knew how to get the best performance from the sculptors, ceramicists and woodworkers who executed his designs. Indeed, nearly every surface inside the auditorium has been adorned with color, texture and relief and, because the walls and ceiling are made almost entirely of stained glass, colored light.

Atop the balcony’s mosaic-clad columns, bronze chandeliers tilt like sunflowers toward the stained-glass sun that seems to float in midair from the ceiling’s inverted dome. The astonishing expanses of glass were achieved with the use of structural steel — invisible beneath so much decoration.

The other pillar of Domènech’s World Heritage status is the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Hospital of the Holy Cross and Saint Paul), set on 40 park-like acres at the northern edge of the Eixample. Heeding the latest theories of hygiene, Domènech envisioned a complex of 20 pavilions to ensure ventilation and access to sunshine. He ingeniously sunk the corridors and service areas of the hospital underground so that patients and visitors in the pavilions and gardens above would feel as if they were in a village — a fantastical one with myriad domes, spires, finials, sculptures and mosaics. Currently, the 12 pavilions Domènech built (his architect son completed the last eight) are being restored; some will become a museum of Modernisme and others offices for humanitarian organizations like Unesco. Until its scheduled opening in 2016, hard-hat tours are offered daily.

With the Modernisme Route’s map and guidebook in hand, you can lead yourself around Domènech’s residential structures in Barcelona, most of which are clustered between the Passeig de Gracia and Carrer Girona. You can stay in one of the grandest of his palatial homes, Casa Fuster, now a five-star hotel, at the top of Passeig de Gracia. In the street-level Café Vienes, you can sip Champagne and admire a vaulted ceiling and a forest of marble columns.

Near the port is the Hotel España, which, though not built by Domènech, had its restaurant, La Fonda España, renovated by him a century ago. It’s just been spruced up and shines anew with Domènech’s strappy wood and ceramic wainscoting, murals by Ramon Casas and a sculptural fireplace by Eusebi Arnau.

Want to see more? Eighty miles south, in the town of Reus, is Casa Navàs, another “complete interior,” which surrounds you the minute you step into the stair hall — a tiny indoor garden of flowers and vines wrought in mosaic, stained glass and carved stone. Throughout the house, the capital of each column features a different floral motif. Most of the rooms contain their original, exuberant furnishings by master craftsmen like Gaspar Homar.

On the outskirts of Reus, the Pere Mata Institute, a mental health hospital begun by Domènech in 1898, was meant to counter the tradition of keeping the mentally ill out of sight. Today you can visit one of the six pavilions, the one that housed “rich and illustrious men,” as the guide explains on the 90-minute tours. The sumptuously decorated men’s pavilion has a billiard room, grand salon and formal dining room. But lest it be confused with a typical men’s club, the delicate-looking leaded glass windows were reinforced with iron to keep patients in.

Upstairs, the rooms contain many of their original furnishings, including clever armoires with basins (and running water) built into them. There were also suites with office spaces (and secretaries) for those patients who still had empires to run.

About 50 miles northeast of Barcelona in the coastal town of Canet de Mar, one can see three charming structures in the space of about 100 yards. Domènech’s mother was from the region and he also had a home here, which is now a museum that displays his drawings and original furnishings. Across the street is the Ateneu Canetenc, once a cultural and political club and now a library.

Perhaps the most satisfying stop in Canet is Casa Roura, a little fortress of a house that is now a restaurant. The facade’s bravura brickwork creates a lively play of light and is further animated by turrets, parapets and gleaming roof tiles glazed in cobalt blue and canary yellow. The old double-height salon with its baronial fireplace is now the main dining room. On par with the rich architectural surroundings is the amazing lunch menu (13.50 euros) — especially the seafood fideua (like paella, but made with pasta instead of rice).

The tour ends where Domènech’s love of medieval architecture may have begun: at his mother’s house. (One of them anyway — the Castell Santa Florentina in the hills above Canet has been in the Montaner family for centuries.) Around 1909, Domènech expanded the original fortified stone house, deftly mixing his neo-Gothic riffs with authentic Gothic architectural elements like columns, portals and arcades “harvested” from a defunct monastery into a modernista masterpiece, one that quite literally spans the ages.

IF YOU GO

IN BARCELONA

For 18 euros, or $23.50 at $1.31 to the euro, a Modernisme Route pack of two guidebooks with maps and discounts for many sites can be purchased at special Modernisme tourist offices in Plaça de Catalunya, Hospital de Sant Pau and Pavellons Güell. Information: www.rutadelmodernisme.com.

Palau de la Música Catalana, Palau de la Música 4-6, (34-90) 247-5485; www.palaumusica.cat. A tour is 12 euros.

Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, San Antoní Maria Claret 167, (34-93) 291-9000; www.santpau.es.

Hotel Casa Fuster, Passeig de Gracia 132, (34-93) 255-3000; www.hotelescenter.es.

Hotel España, Sant Pau 9-11, (34-93) 318-1758; www.hotelespanya.com

IN REUS

Tours of both the Pere Mata Institute and Casa Navàs can be arranged on specific days through the Reus tourism office.

Reus Turisme, Plaça del Mercadal 3, (34-97) 701-0670; turisme.reus.cat

IN CANET DE MAR

Casa Museu Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Xamfra Rieres Buscarons i Gavarra, (34-93) 795-4615; www.canetdemar.cat. Entrance fee: 2 euros.

Casa Roura, Riera Sant Domènec 1, (34-93) 794-0375; www.casaroura.com.

Castell Santa Florentina is a private home but tours can be booked some Saturdays and by appointment. Riera del Pinar s/n, (34-609) 813-339; www.santaflorentina.com.